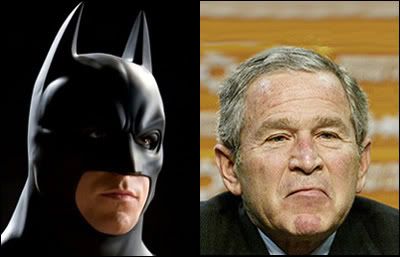

Separted at Birth?

Well, this was fairly inevitable. Batman is our new neocon hero. Wall Street Journal's Andrew Klavan has gone so far as to insist that the caped crusader is none other than George W. Bush.

A cry for help goes out from a city beleaguered by violence and fear: A beam of light flashed into the night sky, the dark symbol of a bat projected onto the surface of the racing clouds . . .

Oh, wait a minute. That's not a bat, actually. In fact, when you trace the outline with your finger, it looks kind of like . . . a "W."

There seems to me no question that the Batman film "The Dark Knight," currently breaking every box office record in history, is at some level a paean of praise to the fortitude and moral courage that has been shown by George W. Bush in this time of terror and war. Like W, Batman is vilified and despised for confronting terrorists in the only terms they understand. Like W, Batman sometimes has to push the boundaries of civil rights to deal with an emergency, certain that he will re-establish those boundaries when the emergency is past.

I had little doubt that the moral ambivalence depicted in "The Dark Knight" would set off alarm bells for civil libertarians and give fodder to fans of the extra-legal. But Klavan (and yes, I find it hilarious that his name evokes that other pseudo-intellectual Cliffie Clavin of "Cheers" fame) has put forth a very shoddy analysis to back his claim.

Let's start with the obvious. Batman does not become a vigilante because of the nature of the criminals he's pursuing, however much like terrorists Klavan imagines them to be. He becomes a vigilante because of a broken system of government and jurisprudence. One which is in bed with the crime families it is supposed to be arresting and prosecuting. All of Gotham is a well-known cesspool of criminality, in which it is an open secret that institutions like the bank the Joker robs in the opening sequence, are owned by the mob. The crime in Gotham is not anomalous or unexpected, like terrorism. It's institutionalized into the very fabric of Batman's universe. Gotham is a city in which nearly every public and private institution is enmeshed in a culture of criminality. The handful of honest pols, police, and prosecutors, are hamstrung by the corruption in their own midst. Now that sounds like the Bush Administration. Batman, for his part, longs for a trustworthy gatekeeper of the public trust, and sincerely hopes that the apparently scrupulous Harvey Dent will make his tactics unnecessary.

Also, unlike Bush, et al., Batman is quite aware that he is breaking some laws. He's not insisting that everything he does is legal and enlisting attorneys to reinterpret the Constitution. He is beset by moral qualms that have never been expressed by that poster child for wrong-headed certitude, George W. Bush.

Batman also fights his own battles. He doesn't send thousands of men and women off to fight and die, after carefully avoiding war in a champagne unit of the National Guard. Bush is more like the wealthy, playboy persona Bruce Wayne adopts to throw people off the trail of his superhero identity.

Although Klavan doesn't specifically address it, the issue of torture has been raised, because of the brutal and sadistic tactics employed by Batman, and in some cases, undertakes under the imprimatur of the Police Dept. It has even been suggested, in some quarters, as testimony to the efficacy of torture. The propensity amongst Republican weenies to confuse movies and television with reality, has been well covered. But more to the point, if we are using "The Dark Knight" as an elucidation of the merits of torture, it would behoove us to recognize that torturing that "terrorist," the Joker, didn't work. In fact it played right into his hands. He used Batman's little chair smashing exercise to do what real interrogation experts have long warned any terrorist would in the event of the "ticking-time-bomb" scenario: Run out the clock.

There is no question that "The Dark Knight" tests the boundaries of major civil liberties questions. But the film, in addition to being set in a virtually lawless environment, also wrestles with those questions, rather than offer pat answers. It does not portray anything like the moral clarity Klavan suggests. Quite the contrary.

0 comments:

Post a Comment